Why We Have a Hulk

When Marvel’s The Avengers finally stormed theaters in 2012, it was met with near-universal acclaim. Everyone had their favorite characters and moments, but the one who seemed to get the most attention was the Hulk. Unlike the earlier cinematic incarnations of the not-so-gentle giant, this was a Bruce Banner less concerned with containing – and ultimately ridding himself completely of – the monster lurking within him and more eager to help others, fight bad guys and even pal around with his fellow Avengers. The Hulk was being presented not as an object of fear, but as a savior, a hero who fit right in with Captain America and the rest. By and large, the reaction was elation at finally getting the Hulk people wanted to see on screen. The thing of it is, although there were other factors that allowed this Hulk to fit in with his teammates (Joss Whedon’s skill at balancing tones, a threat big enough to require a Hulk-sized response, Tony Stark being Tony Stark and egging Banner on), the main reason why this new, fun Hulk is possible is the character arc that occurs in the retroactively-underappreciated The Incredible Hulk.

I say retroactively because, when it was first released, people really seemed to love The Incredible Hulk (the people who saw it, anyway). After Ang Lee’s much slower, much dourer film, it was seen in much the same way Ruffalo’s Hulk is now, as a burst of desperately needed fun. Compared to the Hulk who runs with the Avengers, though, Norton and Letterier’s version is homework and was quickly marginalized by a fandom too punch-drunk in love with their new darling to understand how necessary it was for him to have gotten past his baggage.

*Spoilers for The Incredible Hulk and The Avengers*

In The Avengers, Banner is at a place where he can – for the most part, as Natasha unfortunately experiences first-hand – control his inner monster. He doesn’t Hulk out at the slightest provocation, and he’s confident enough that he will even allow himself to remain in high-stress situations despite the reservations of others. (“Yes, and I’m not leaving because suddenly you get a little twitchy.”) He spends his time before SHIELD recruits him not isolating himself and trying to get rid of the Hulk but administering medical care to poor people in India. When the final battle comes, Banner is even able to make the choice to transform himself into the Hulk, a moment of graceful beauty contrasted with the jerky horror of his Loki-induced change on the hellicarrier. And he’s no longer a mindless brute but a full member of the team, focusing all his rage on the Chitauri, helping out his fellow Avengers and even specifically rescuing an office full of innocent people. (Quick sidebar: because of the world’s fear and distrust of the Hulk, it means so much more when he saves lives than when, for example, Captain America does it; it’s the opposite of what’s expected of him, and it actually changes minds and battles misconceptions and prejudices). To be clear – in case the introduction sounded a bit defensive – I’m not deriding any of this for a second. I love the newer, more fun Hulk and can’t wait to see him again in Age of Ultron. However, it’s important to understand why this Hulk is around, as well as that, in certain fundamental ways, he’s not actually all that different from his direct predecessor.

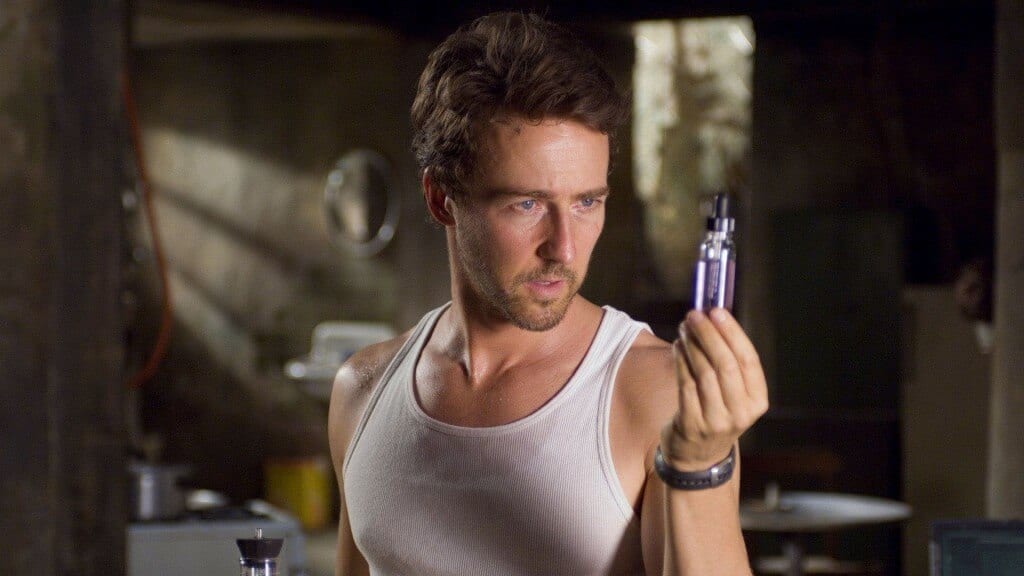

The Bruce Banner of The Incredible Hulk is determined to rid himself of the monster once and for all. He’s lying low in Brazil, seeking out ways to keep the Hulk at bay while communicating via the internet with a scientist in the States to find a medical cure for himself. He keeps a heart monitor strapped to his wrist, which he’s constantly checking to make sure he isn’t getting too excited. He visits some kind of meditation expert (who can do freaky-looking things with his abs; how looking at that would keep anyone calm, I have no idea) to learn to control his emotions. It seems to work for a time, and Banner goes quite a while “without incident.” When General Ross and his forces come knocking, though, he realizes how futile his efforts have been. It isn’t even the soldiers who get him to change; it’s a trio of jerks from his factory job who decide to rough him up a little. All of his attempts at overcoming his anger have failed if he can’t hold in the Hulk in the face of three punks.

In the face of this overwhelming defeat – and think about that; Bruce takes down an entire team of elite Special Forces commandos and he considers it a loss – Banner decides his only hope lays in aggressively pursuing a scientific cure. After being reunited with Betty Ross and laying waste to more of her father’s quixotic attempts to ensnare him, he links up with the guy at the other end of his internet chats: Mr. Blue, alias Samuel Stern (whom I’d like to see return as the Leader someday, Marvel Studios! Ditto Liv Tyler’s Betty, who conveys so much of her soul in a mere glance), a scientist who is fascinated with Banner’s condition and wants to help cure him more out of pure curiosity than a desire to prevent disaster. Avoiding a bunch of science terms that probably have little-to-no real world meaning because the film is dealing with an “enormous green rage monster” – sometimes you have to defer to the master – they induce a Hulk-out and administer a possible antidote Stern has developed, with the intention of removing the Hulk for good – a process that could very well kill Banner. Like the meditation techniques, though, it doesn’t work and Banner is still the Hulk.

Why don’t any of these attempts to contain or destroy the Hulk succeed? Aside from the fact that it would lead to some really boring superhero movies, the methods Banner uses are all based on suppression, with the desired effect being repression. He’s so afraid of the Hulk that he wants to push his anger into the deepest hole he can dig, or have the monster removed from him completely. These things don’t work, though, because the Hulk is a part of who he is. Suppressing an aspect of yourself will not make it go away; it will only exacerbate the severity of its manifestation when it inevitably breaks free of your inadequate shackles. Banner can no better get rid of his anger than anyone can, say, stop liking ice cream. It’s part of who he is, and it will always be there. His aborted sex with Betty is the perfect representation of this (wrapped in a fun joke, in the Mighty Marvel Manner); he hasn’t seen her for a long time, he still loves her as she does him, they both want to be together, but he suppresses his desire because he’s afraid that it, like his anger, will trigger the Hulk. (Thank heaven Banner doesn’t take the metaphor further and attempt to medically prevent his sex drive like he does the Hulk.) He has been denying his emotions in order to control them, but all he’s really done is bottle them up, creating so much pressure on himself that the Hulk has no choice but to come out.

The climax of the film is when he finally gets it, or at least begins to get it. When Emil Blonsky becomes the Abomination, Banner knows that pig-headed General Ross will never be able to stop the gamma-infused supervillain. The only way to save Manhattan is for Banner to stop fighting his emotions and embrace them. For the first time ever, Banner actually elects to become the Hulk; the monstrous embodiment of his rage is the desired result rather than the unavoidable consequence. It’s also the first time that Banner sees the possibility of the Hulk ceasing to be a monster and becoming a hero. (It’s worth noting that others have viewed the Hulk in this way; Doc Samson, for example, tells General Ross of the Hulk, “He protected her; you almost killed her” in reference to the battle that nearly claimed Betty’s life, and Stern calls Banner’s blood “Promethean fire” because he sees the potential benefits to mankind.) He explains his plan to Ross and Betty by saying he may not be able to control the Hulk, “but maybe aim it.” It’s the kind of idea born of necessity, as many great ones are, and Abomination’s rampage finally gets Banner to overcome his fear of the Hulk and try to use his alter ego for good. And it works! It’s not perfect; Hulk still causes lots of destruction and his big rescue moment involves saving Betty, whom he always protected in the past, but he is able to stop Abomination from slaughtering an awful lot of people, and with Betty’s influence he even holds back from killing his enemy. He’s not where he will be when played by Mark Ruffalo, but it’s a start.

And that’s the whole point; this is the start of Banner’s ability to manage the Hulk. He wouldn’t have been able to reach the point of control he has in The Avengers without the journey he takes in The Incredible Hulk, and that result would have no weight if we didn’t see the steps Banner took to get there. In the final moments of the film, Banner is shown meditating, and he seems to force a transformation on himself, smiling as his eyes go green. This is the culmination of all he’s learned in the film, the “secret” he constantly teases in The Avengers and eventually explains to his new friends: “I’m always angry.” Suppressing his emotions was doomed to fail; it was in embracing them that he is finally able to learn control, and the fight with Abomination – in addition to the futility of his constant attempts to bury them – is what makes him realize it. If The Avengers existed without The Incredible Hulk, that incarnation of Banner would be a payoff without a setup, ultimately meaningless aside from the pleasing aesthetics.

Banner’s drive to help people, on the other hand, is a trait he always had; like Hulking out, it was his fear that kept him from acting on it in the most practical way available to him. When General Ross tells Blonsky about the gamma experiment that created the Hulk, he reveals that Banner was unaware of the military’s goal of building better weapons, thinking instead that he was developing a stronger protection against radiation, and that he wouldn’t have helped had he known the truth (this is similar to Banner’s outrage when he discovers SHIELD is trying to weaponize the Tesseract in The Avengers); the Hulk is the result of Banner’s desire to protect. When he’s in Brazil, he sees a woman who works with him being harassed by three letches and, though he knows it’s a big risk, he cannot fight his urge to help her. Every time he explains the importance of containing the Hulk, it’s because he wants to keep innocent people from being hurt. The worst thing Ross did to Banner was put him in a position where he is unable to be the hero he wants to be. He’s so good-humored in The Avengers because he’s finally at a place where he can do what he’s wanted to do all along and help those in need. This isn’t a different side of Banner but rather the same Banner finally reaching his full potential, unencumbered by fear and doubt.

This is why Blonsky is such a great villain. While Banner is afraid of the Hulk’s power, Blonsky is enamored with it. He begins the film not as an evil man, but certainly one more aggressive than Banner. He’s “a fighter,” as he tells Ross, uninterested in promotion because it would take him away from the violence he craves. When Blonsky sees the Hulk, though, it triggers a lust in him and as the film goes on he grows more and more obsessed with possessing the Hulk’s strength, envisioning a world where he would never have to back down from a fight. The super soldier serum gives him just a taste of what Banner feels when he becomes the Hulk, and Blonsky needs more. He isn’t satisfied until he forces Stern to inject him with Banner’s blood, which mixes with the serum already inside him and gives him that power he covets. The Abomination is everything Banner fears the Hulk is, and as he watches the destruction he knows he finally must confront that nightmare scenario himself; Abomination, then, acts as the manifestation of what Banner has spent the entire film fighting, avoiding, relentlessly trying to make not so, and the conclusion Banner reaches is that the only way to conquer his fears is to embrace them. He chooses to turn into the Hulk, just as Blonsky chooses to become Abomination, and that’s why he’s able to save New York from his evil counterpart. In voluntarily transforming, both men are able to act on their true desires: Banner’s to protect, Blonsky’s to destroy. Again, this is only the first step for Banner, and he has more mastery of his emotions in The Avengers, but it takes him longer to figure this out than Blonsky because Blonsky never has the same trepidation as Banner; he jumps into gamma monster mode with both feet and lets it engulf him. (“You don’t deserve this power!”) It isn’t the power of the gamma rays; it’s Banner’s heart that makes him a hero, just as it is Blonsky’s lack of one that makes him a monster.

Bruce Banner’s crowd-pleasing characterization in The Avengers wouldn’t be possible, or nearly as enjoyable, without his arc in The Incredible Hulk. The earlier film compliments the superhero team-up beautifully, setting its hero on a journey that reaches its satisfying conclusion when the Hulk assembles with the rest of Earth’s Mightiest Heroes.