Pulling Pistols and Whistling Dixie

Clint Eastwood is one of the great modern filmmakers, a man whose directing talents have landed him many Oscar nominations and widespread critical acclaim. Those accolades don’t usually extend to his work in front of the camera, however; it may be the parts he often played in his younger days, the cops and cowboys and assorted other action roles, but whatever the case, it’s a shame. Eastwood is an excellent actor, and it miffs me to see his talent so often dismissed, even by his fans (he was, to be fair, nominated twice for Best Actor Oscars, but he was never considered a serious contender for either). Just because a movie is fun and exciting, as many of Eastwood’s are, doesn’t mean that there is no skill in the performances, no humanity to be found between (or even within) the shootouts. To that end, these are the roles that I consider to be Clint Eastwood’s best, and why I think they show his skill as an actor.

*Spoilers for all of these movies, but I’ll list them before each section, so if there are any you haven’t seen, you can skip around.*

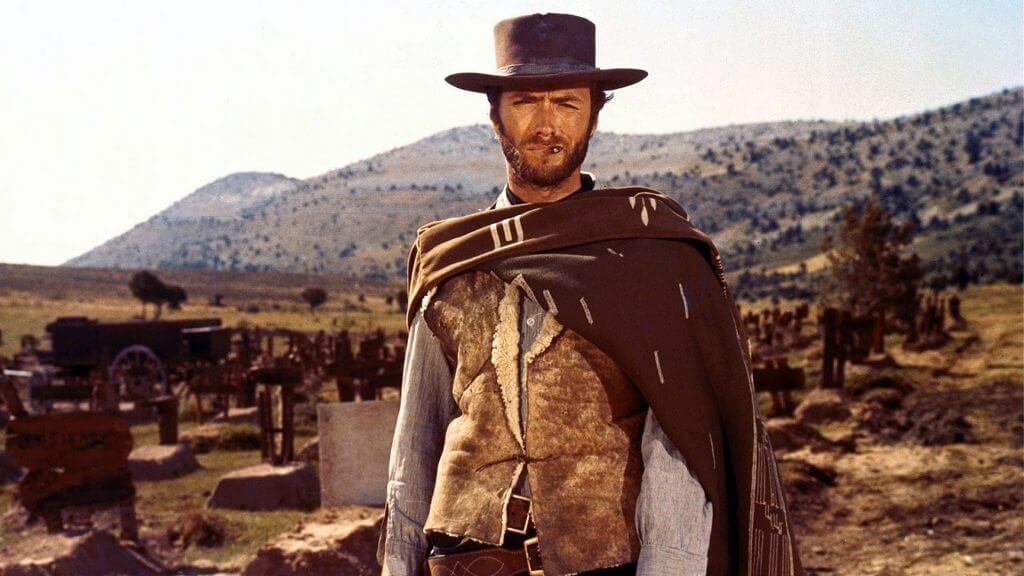

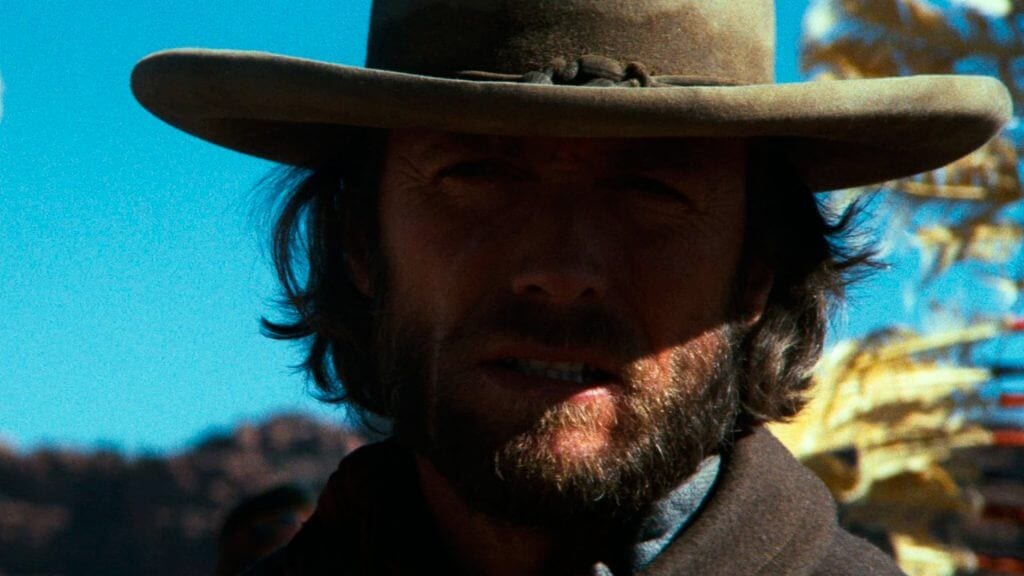

The Man with No Name – A Fistful of Dollars (1964), For a Few Dollars More (1965), The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

One of Clint Eastwood’s two most iconic characters (no points for guessing the other one), the Man with No Name changed the image of the Western hero from the upright, stalwart cowboy in the John Wayne or Gary Cooper mold to the mysterious gunfighter who drifted from town to town seeking out violence. While the old guard were mostly lawmen who proudly wore their white hats, Eastwood’s ilk dressed more like the bad guys and had no use for badges or the law. In A Fistful of Dollars, the patriarch of one of the two warring families is actually the town sheriff, and upon coming across him, Eastwood’s stranger scoffs at his threats and flippantly puts him in his place. The sheriff’s corrupt clan, the Baxters, is at odds with a Mexican crime family called the Rojos, and the innocent townspeople are getting caught in the crossfire, but the Man With No Name involves himself in the conflict only because he sees the potential for financial gain in playing both sides against each other. For a Few Dollars More has the Man With No Name acting as a bounty hunter (or “bounty killer,” as the characters in the film are more fond of saying), chasing down criminals only to line his pockets. When he teams up with fellow bounty hunter Colonel Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef, a terrific match for Eastwood with his devilish eyes and gravelly voice), he’s actually the less moral of the two, betraying Mortimer more often than he is betrayed himself. His greed is on even fuller display in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly when he alternately teams up with and races against a man he thoroughly dislikes (Eli Wallach) to get at a stash of buried gold. No matter the moral stakes, The Man With No Name is always initially motivated by his love of money.

It never stays that way, however. Though he may want his payday, at heart the sarape-wearing gunslinger is a decent man, and when he sees an injustice grave enough, he will fight to correct it. Ramón Rojo (Gian Maria Volonté), the main villain of A Fistful of Dollars, has taken a woman from her husband and son and claimed her as his own; the entire town is aware of this and does nothing, because they know anyone who defies the Rojos will be killed. But, after trying his level best to turn a blind eye, the Man With No Name cannot let this stand, and he sacrifices his undercover role inside the Rojo outfit to free the woman and return her to her family. When asked why a man like him would help such lowly peasants, he says, “Why? ‘Cause I knew someone like you once. There was no one there to help.” It’s one of the few small insights into his past, but clearly he’s seen some suffering in his time and, when possible, he’ll snuff out what little of it he can. When he learns the reason why Colonel Mortimer is so gung-ho to kill El Indio (Volonté again; many actors appear in different roles throughout the trilogy, including Van Cleef, who would return as the villain of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) in For a Few Dollars More, he stops double-dealing the man and even facilitates Mortimer’s well-earned revenge. In The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, greed is his motivation throughout, but he does have a moment of compassion when he comes across a dying Confederate soldier, covers the fellow with his jacket and gives him a puff of his cigarillo before the young man dies; it is from this soldier that the Man With No Name acquires his trademark sarape, making it a symbol of the good of which he is capable (and lends even more weight to the doom portended by his throwing it over his shoulder before a gunfight; he is discarding the object that represents his mercy to make it easier to draw his death-dealing pistol). While seemingly a self-interested scoundrel, the Man with No Name is actually much more complex.

Clint Eastwood conveys that complexity with a subtlety he’s not often credited for having. When the Man with No Name frees Ramón’s enslaved woman, his normally-even-toned voice takes on a sudden harshness as he orders them to leave town and cross the border as quickly as possible; he’s at ease when making money off the graves of dead bad guys, but he’s desperate when trying to save innocent people. When he gives Mortimer a shot at justice, he doesn’t change a thing about his voice or mannerisms, instead letting his actions speak for themselves. There is no urgency to the situation, meaning there’s no reason for him to drop his cool demeanor. The same is true when he gives the dying soldier a last smoke. The man is not in danger, as his death is inevitable based on his wound; why waste time getting emotional about it? Once the soldier has passed on, he begins to retrieve his coat, then decides he’d rather not take back what is perhaps the first gift he’s ever given (and the first good deed he’s ever done), patting the young man once on the shoulder and taking the junky sarape for himself while leaving behind his thick coat. These small gestures convey more than words or exaggerated body movements ever could, and Eastwood employs them to give the Man with No Name some color while retaining his mystique. It’s a great performance, stretched across three movies, and the reason why people still remember the Man with No Name today (well, that and the music).

Lt. Morris Schaffer – Where Eagles Dare (1968)

Clint Eastwood is considered the poster boy for the strong, silent type (which makes his reputation for having so many great lines even more amusing), and if any of his roles personifies that aspect of his image, it’s Lt. Schaffer. Schaffer is the lone American on an otherwise British team of soldiers sent on a mission to scale a mountain in the Bavarian Alps and infiltrate a Nazi castle to rescue an Allied general captured by the Germans. Expectedly, things don’t go as planned and soon it’s just Schaffer and Major John Smith (Richard Burton) against an army of Hitler’s finest. While Schaffer gets a line in here and there, Smith does virtually all of the talking throughout the mission, taking the lead in convincing the Germans that the two heroes are Wehrmacht officers. Schaffer, conversely, is the man of action, setting explosives around the castle and gunning down Nazis left and right. It’s exciting, and Eastwood handles himself as expertly as always while under fire, but the mostly physical performance is even more noticeable because he’s standing next to Richard Burton’s fast-talking spy. Burton’s is the showier role, and Eastwood never tries to horn in on his co-star’s theatrics, instead remaining low-key and allowing the contrast to make them both look better, as well as to elevate the tension; Smith’s fight with the traitors on top of the cable car, for example, is all the more harrowing because he hasn’t been established as the tough guy Schaffer has.

Schaffer also serves as the audience stand-in, always being kept in the dark as to the true nature of the mission, learning things at a similar pace to us, unlike Smith, who is the only person in the movie with all the information (except for his immediate superior back in England, who has about five total minutes of screen time and, as such, is barely a factor in the plot). He doesn’t even know why he’s on the team to begin with, since he’s an American soldier and the mission is “primarily a Brit operation.” At one point Smith does let Schaffer in on the real plan, but this happens off-screen and, when Smith springs his trap in the midst of the head Nazis in the castle (a great, long scene), Schaffer says, “Major, right now you’ve got me about as confused as I ever hope to be,” indicating that Smith still hasn’t told him everything. In the final moments of the film, when Smith exposes Colonel Turner as the leader of the Nazi spy ring, the reason for Schaffer’s presence is revealed: all of Turner’s traitors were MI6 agents, meaning Schaffer, as an American, could be trusted not to be a part of it. As Smith relates this to Turner, Schaffer’s body language – slight gulping in his throat, glancing at the floor as he furrows his brow – suggests that he’s hearing it for the first time as well, and Eastwood makes these tics subtle but noticeable, maintaining the illusion of the film while apprising the audience of Schaffer’s mindset. Usually, our gateway into a story like this is a very average-seeming character, as in awe of the titans surrounding him or her as we are, but in Where Eagles Dare we get to experience the adventure vicariously through a grand hero like Clint Eastwood, and you just can’t beat that.

Inspector “Dirty” Harry Callahan – Dirty Harry (1971), Magnum Force (1973), The Enforcer (1976), Sudden Impact (1983), The Dead Pool (1988)

Perhaps even more than the Man with No Name, Clint Eastwood is most associated with the role of renegade San Francisco cop Harry Callahan. The squinting, rule-breaking, .44-Magnum-wielding nigh-vigilante who gets “every dirty job” struck a chord with audiences, even as he alienated critics. Dirty Harry famously caused the nation’s reviewers to have heart palpitations due to its hero’s flagrant crossing of legal lines in his quest for justice, and the film was accused of being an endorsement of fascism, but really it’s about a man who reaches his breaking point when confronted with a psychopath who wantonly murders innocent people and hides behind a criminal justice system tailored to favor the accused in order to escape punishment. More than any other element of the movie, Eastwood himself makes this clear through his performance.

As the killer (Andrew Robinson), who calls himself Scorpio – an allusion to the Zodiac Killer, whose rampage haunted the citizens of San Francisco in real life – makes demands of the city in exchange for his obeying the law, Harry is frustrated by the willingness of the bureaucracy supposedly representing the people to give in to extortion (a theme that will return later in the series). When Harry finally gets his hands on Scorpio, the madman has a kidnapped girl stashed somewhere and, instead of giving up her location, demands a lawyer. Enraged, Harry tortures Scorpio to get the information, and in this scene it’s Eastwood’s acting that counters the cries of fascism leveled against the movie; he makes clear Harry’s frustration at being impotent to help an innocent woman and his anger at being faced with a demonic little thug who demands rights his victim has been denied. Who speaks for the girl who is rotting in a pit? Harry Callahan decides he will, because no one else can. The film isn’t a plea to suspend Miranda, it’s a reflection of how living in a society that has these laws – necessary though they may be – can tax the souls of the righteous, and Eastwood communicates that with his expression as Harry presses his shoe onto Scorpio’s gunshot wound. In fact, the girl isn’t even rescued but found dead, so all Harry’s torture accomplishes is getting Scorpio freed on a technicality. (Of course, Harry gets him later; this is Clint Eastwood we’re talking about.) The reason Harry Callahan is so beloved isn’t that he’s some Gestapo bully who does whatever he wants; it’s that he is a reflection of our own anger at the limits of legal justice. As with Where Eagles Dare, Clint Eastwood is us, just much more capable.

The first sequel, Magnum Force, does a bit of damage control by making the villains a squad of rogue cops who’ve turned themselves into a hit team, gunning down anyone they deem worthy of violent retribution. Their actions actually change Harry’s mind, if only a little bit. Early in the film, in response to their slaying of a group of mobsters, he says, “Couldn’t have happened to a nicer bunch.” As they continue their executions, though, they start killing more than just killers, gunning down prostitutes and even just random party guests. When Harry confronts them in a parking lot, their identities finally revealed to him, he sarcastically calls them “heroes” while telling them they’ve “killed a dozen people this week.” Harry Callahan isn’t a mindless executioner, and though he does bend – and sometimes even break – the law, he recognizes the dangers in stepping too far over the line; again, he’s a reflection of our own desire for justice, now mixed with our fear of a police force with no rules.

The Enforcer returns to the theme of obstructive bureaucracy. Early on, Harry is faced with an influx of women into the police department, which he opposes because he sees it as an attempt by the brass to look good instead of putting qualified officers on the streets. Soon after, he’s partnered with Kate Moore (Tyne Daly, by far Harry’s best partner) and, though initially hostile towards her, he eventually comes to respect her. Harry isn’t opposed to women being cops in general; he just wants them to earn it, not to be used as props by politicians. Later, when he investigates the robbery of a weapons stockpile, his and Kate’s efforts to find the real criminals are hampered by his superior, Captain McKay (Bradford Dillman, a good sport in a thoroughly unlikeable role), who insists on arresting a group of, as he calls them, “black militants,” because he knows it will play well on the news. When the real perpetrators kidnap the mayor and hold him hostage on Alcatraz Island (because of course they do), McKay is ready to pay them the ransom. Harry and Kate take matters into their own hands and save the mayor, killing all the villains, and the final moments see McKay landing on the island in a helicopter, announcing that he has the kidnappers’ money as Harry steps through the tangle of dead criminals with the rescued mayor. Harry is the vessel of our frustrations once more, this time with an authority primarily concerned with its own image and all too ready to hand over society to criminals.

Next is Sudden Impact, where Harry is faced with tracking down a killer who is herself a victim. Years before the start of the film, Jennifer Spencer (Sondra Locke, who, during this period, was Eastwood’s romantic partner and showed up in pretty much all of his movies; some people criticize this, but I think she’s a decent actress) and her sister were raped by a group of punks under a boardwalk. Now, she’s hunting them down and killing them one by one. Harry – in hiding because he’s angered the Mafia – lends a hand to the local cops investigating the murders, but the more he learns, the more he begins to sympathize with Jennifer. Is she the real villain, or are her victims? As always, Harry is a reflection of our own humanity, looking at Jennifer the same way we would and wanting her attackers to be paid back. In her, he sees a bit of himself, striking out at people that the law isn’t willing to deal with (due to one of the rapists being the police chief’s son). In the end, he covers up her crimes, blaming the murders on the worst of the rapists, because he knows she’s not a mindless killer and that her going to prison isn’t justice.

The Dead Pool, while a very fun movie and definitely worth seeing, doesn’t quite have the same (sudden) impact as the first four, and Harry is no longer one of us but a celebrity, part of a list of famous people who are being targeted for murder by a crazed fan. Society’s obsession with celebrity is examined, but not through Harry. He’s the outsider here, the guy who doesn’t care how many movies the victims have made, and as such he’s removed from our sensibilities for the first time in the series. No matter what, it’s still fun to watch Clint Eastwood kill some bad guys, but a piece of what makes Harry Callahan so endearing is lost this time out.

Coinciding with his ties to the audience’s humanity, Harry Callahan is almost built to be a legend, more so in the sequels than the original. He breaks the rules with no thought spared for the consequences. He spits in the face of authority. He uses “the most powerful handgun in the world,” an element played up even by the sound effects; while all the weapons around him are pop-pop-popping like cap guns, Harry’s .44 Magnum roars with the thunder of the gods themselves, striking down evildoers with a satisfying finality. Each film also has a scene early on where Harry stumbles upon a crime in progress – usually one with some very real victims – and makes short work of the hoodlums. The exception is the bank robbery in Dirty Harry; in this sequence, Harry realizes the thieves will escape if he doesn’t intervene and shoots them down in self-defense, scaring the sole survivor into surrendering but never intending to kill him. This serves as a contrast with Harry’s brutality in opposing Scorpio, showing how it’s the stress of Scorpio’s tactics that push him to extremes to which he normally wouldn’t go.

Then there are the catch phrases. In addition to the usual plethora of Clint Eastwood one-liners, Harry has a catch phrase he says once in the beginning and repeats at the end of the film, usually just as he’s about to blow away the bad guy (The Enforcer being the one exception, at least as far as I can tell; I’ve watched it many times, and I’ve never been able to pick out the repeated line). It’s fun seeing which one will come back around, and what it means to the theme of the movie: asking the “punk” if he feels lucky in Dirty Harry, as in, does he think Harry has been emotionally taxed enough to kill him; acknowledging that every man has a limit to how much lawbreaking he’ll endure in Magnum Force; wanting a true lowlife to “make [his] day” in Sudden Impact by giving him a reason to open fire; acknowledging the criminal’s underestimating of him in The Dead Pool by informing them how “out of luck” they are (this one isn’t thematic so much as it’s just really cool). These lines add to the mystique of Harry Callahan.

It took an actor like Clint Eastwood to capture Harry’s humanity as well as his iconography. He’s a larger than life performer with a soul, and he can express the latter without undermining the former, just like he did for the Man with No Name. When Harry loses his composure and acts out in futility, inwardly cursing his own ineffectualness, he remains an imposing figure, someone we want in our corner when the enemies are storming the gates. He’s as believable wielding the .44 Magnum as he is mourning a dead partner, and his anger at the underworld’s predators is as palpable as his anguish at the pain felt by their prey. Eastwood keeps one foot in both camps, and if not for him, “Dirty” Harry Callahan would be a footnote in cinema history rather than an indelible part of it.

Josey Wales – The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976)

While we meet most of Clint Eastwood’s Western heroes more or less fully formed, The Outlaw Josey Wales shows how a legend is forged. Josey is a simple man content with living a simple life, wanting no part in the Civil War as he tills his land with his family by his side. The War finds him, though, when a squad of marauding Union soldiers called the Redlegs murder his wife and son (and, it’s implied, rape the former), set fire to his home and slash his face, forever marking his body and his soul. Josey buries them, saying a prayer as he affixes a wooden cross to mark their grave, but breaks down before he’s done, unable to complete the prayer and pulling down the cross as he weeps. In this moment, Josey loses his humanity, his religion, everything that makes him who he is, and Eastwood plays the anguish perfectly. It’s much less subtle than the typical flashes of humanity his characters show, and he adapts well to the shift in tone. Once the dead are buried, Josey cries no more tears and teaches himself to shoot, then joins up with a ragtag Southern militia to wage war, getting himself a reputation as one of the deadliest killers the Confederacy has. When the war ends and his superior Fletcher (John Vernon, who also played the mayor in Dirty Harry) advises the group to surrender to the North, Josey refuses, even though holding out means he’ll be hunted to his last days. Josey doesn’t care about living anymore because he has no reason to go on. The War was enough to sustain him, but without that he’s already dead.

Or so he thinks, anyway. Josey Wales may have buried his soul, but it yet lives, and he discovers throughout the film that he can’t quite cast it aside. When the Redlegs turn on the surrendering Confederates, Josey jumps into action and annihilates a good number of them with a Gatling gun. He’s ready to stay in the fray, knowing that he’ll eventually be killed, until Jamey (Sam Bottoms), the lone survivor of the massacre, runs off on his own. Jamey is wounded and will never make it by himself, so Josey goes after him, fighting to survive so he can protect a dopey kid with a bullet in his gut. Soon after Jamey succumbs to his wound, Josey meets Lone Watie (Chief Dan George, outstanding in the role), a Native American drifter, and Little Moonlight (Geraldine Keams), a squaw outcast living in indentured servitude to a shopkeeper. Later, he adds Laura Lee (Sondra Locke again) and her Grandma Sarah (Paula Trueman) to his roving band, and the motley crew end up becoming something of a family. The disparate strangers all see something admirable in Josey, and they stick with him because they genuinely like him, regardless of his violent reputation. For his part, Josey begins to care for all of them too, and despite his insistence that he pays life and death no mind, he protects them as the patriarch of any family would his own blood. Josey Wales doesn’t get his humanity back so much as he discovers he never really lost it.

This is what compels him to leave once they’re all settled in Texas; Josey fears that the same trouble that befell his first family will find this one as well, and no matter how disappointed they are, he’d rather they hate him than die for him. But when Terrell and the last of his Redlegs arrive to finish him off, Josey’s family doesn’t die for him; they fight for him. Just as he trained them to do when he anticipated a Comanche attack, Lone Watie, Laura Lee, Little Moonlight and even Grandma take up arms and shoot down the men who would kill them, and Josey is spurred on by their vigor, finally able to conquer the men who shadowed him with death, even running Terrell through with his own sword – the very one that marked Josey so long ago. It’s through their love that he conquers his fears, and that’s why I believe with everything in me that he goes back to them at the end. (I know he does so in the book, but this is a different entity, despite being a close adaptation, and should be taken on its own merits; that being said, the book is excellent and you should seek it out, as well as its sequel.) They saved him as much as he saved them, and together they’ve built a real home.

As opposed to the opening scenes, the rest of the film returns Clint Eastwood to the subtlety that is his stock in trade and he uses slight facial tics to show the lengths to which Josey goes to keep himself at a distance, and the annoyance he feels when he realizes he can’t. When first Little Moonlight and later Laura Lee are in danger of being raped, Josey’s disgust at the triggered memory flutters in Eastwood’s eyes, and it spurs him so much that he almost takes hasty action to save Laura Lee, stowing his gun only when he is assured she won’t be violated. (This allows for one of the classic Clint Eastwood scenes, presaged by Lone Watie’s “Get ready, little lady. Hell is coming to breakfast.”) As he journeys across the American frontier and meets his new friends, Josey’s demeanor lightens little by little until, when he finally settles down with them, he is almost jovial. It feels real because it happens gradually, and that’s all on Eastwood. He brings the pain, the anger and the joy to Josey Wales, and in doing so he creates one of the great Western heroes.

William Munny – Unforgiven (1992)

In his final Western, Clint Eastwood – in one of his two Oscar-nominated roles – plays William Munny, who was once the most feared outlaw in the West (sound familiar?). Unlike Josey Wales, the Man with No Name and the many other cowboy legends in Eastwood’s repertoire, though, Munny is not romanticized. He isn’t known as a hero, but a man who “killed women and children; killed just about everything that walks or crawled at one time or another.” As Unforgiven begins, though, we see Munny in his twilight years, and he’s no longer an outlaw; he’s a pig farmer, wrangling hogs with his two young children. Munny gave up his evil ways when he met his late wife Claudia, and settled down to live a quiet life with his family. With Claudia gone, Munny lives under her shadow, ashamed of his past and separating himself completely from the man he was. When the Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett) comes to him with an opportunity to earn $500 on a bounty, he turns the offer down because his wife “cured [him] of drink and wickedness.” Times have gotten tough, however, and with his pigs dying of fever Munny will soon have no way to feed his kids. Reasoning that it was the whiskey he drank that caused his evil, and that the men with the price on their heads deserve to die, he collects his old partner Ned (Morgan Freeman) and saddles up with the Schofield Kid to once more deal out death.

Throughout his journey, both Munny and those he encounters recall his violent actions, and each mention wounds him. He doesn’t protest, but he insists that he isn’t that killer anymore, that he loves his wife and kids, that he no longer drinks. More than the others, though, Munny is trying to convince himself, and this comes across with the lack of conviction with which Eastwood recites these lines. He isn’t nearly as sure as he declares he is that he’s no longer an evil man, and his constant repetition is almost like a prayer, incanted to assure himself that the devil is gone from him. His destination is called Big Whiskey because Munny’s hunt is bringing him face to face with the demons of his past, the demons for which he blames his drinking. He is in the middle of everything that once corrupted him, but he abstains from it all; he doesn’t take a drop of alcohol, he doesn’t take the hookers up on their offers of free sex, he doesn’t defend himself when Sheriff Little Bill (Gene Hackman, who won an Oscar for this role) beats him half to death, and he insists that Ned and the Schofield Kid can do the shooting once they locate their targets. He is forcing himself to dance as close to the fire as he can without getting burned, and the true reason is finally revealed when he has his fever-induced dream: he sees the Angel of Death coming for him, as well as the rotting corpse of his wife, and he fears the death he richly deserves, the death that seems imminent. Usually the toughest of the tough, Eastwood shows a palpable fear as he faces judgment for his crimes.

That judgment doesn’t come, though. Munny recovers and continues the search with his partners. When they corner the two thugs in a valley, Ned wounds one, but he can’t finish the job; for all his moral compromising, Ned can’t kill again. It falls to Munny, and he takes the shot, giving the bandit a slow, painful death. Ned leaves, walking the straight and narrow path that Munny has now all but abandoned, and for his virtue, Ned is tortured and killed by Little Bill. This is the catalyst that gets Munny to come to terms with who he is. A good man dies horribly while an evil one lives and prospers, and it illuminates for him the fact that there is no cosmic sense of justice, no punishment for crimes committed; there is just the random chaos of reality. Before heading back to Big Whiskey to avenge his best friend, Munny takes a few swigs of the drink he’s denied himself, the symbol of his dark past, but he doesn’t get drunk. When he shows up at the saloon, Munny is stone cold sober, unable to blame alcohol for his actions. He’s finally embraced his past and married it with who he’s become since meeting Claudia. He wipes out Little Bill and his deputies, even shoots the unarmed owner of the bar where Ned’s body is strung up. (“Well, he should’ve armed himself if he’s gonna decorate his saloon with my friend.”) When he leaves, he orders the townspeople to give Ned a proper burial and to stop hurting women, lest he return and kill them all. He’s embracing his inner violence, but he’s also fighting for a cause better than lining his own pockets. He is now a man who loves his wife and children, a loyal friend, a champion of justice and an unholy killer, all in one package, and in this final scene Clint Eastwood acts with a confidence that makes you feel each facet of William Munny.

Frank Horrigan – In the Line of Fire (1993)

With this film and Unforgiven before it, Clint Eastwood began not only embracing his advancing age but incorporating it into his films. Here he plays Frank Horrigan, a veteran Secret Service agent who was on the job in Dallas when President Kennedy was murdered. The assassination has haunted him ever since; it drove him to drink and caused him to lose his wife and daughter. Now, he works undercover to arrest counterfeiters, whiling away the back end of his career in a less stressful department of the Service. But all that ends when he gets a phone call from a mysterious stranger who refers to himself as Booth (John Malkovich, who is, hands down, the best villain Eastwood has ever faced) and expresses a desire to kill the current President. Booth sees in Horrigan his opposite number, and he wants to give Horrigan a chance to redeem himself by stopping Booth and saving the President. Horrigan is, of course, all too happy to take Booth up on his challenge and finagles his way back onto the President’s detail so he can properly face his nemesis.

As much as Horrigan is testing his skills against Booth, though, he’s also facing his doubts about his ability to protect the President. He’s devoted his life to a willingness to sacrifice himself for another person, but when Lee Harvey Oswald killed Kennedy, he missed his moment. There are rumors that Horrigan saw Oswald for a split second before the bullet was fired and hesitated, and while it’s never confirmed or denied, his actions throughout the movie indicate that it could very well be true. As Booth observes, Horrigan doesn’t want to die; he has a chance to finish off Booth, but it would mean his own death, so he lets the killer live and ends up getting his partner and protégé Al (Dylan McDermott) killed. Horrigan is afraid of facing that decision again and becomes paranoid in his zeal to stop Booth before the President is caught in the maniac’s crosshairs; all this does is get him removed from the President’s detail. In exile he figures out Booth’s plan, and it once again comes down to Horrigan, the President and a lone gunman. This time Horrigan takes the bullet, saving the President and redeeming himself for a lifetime of failures.

What makes Horrigan such a wonderful character is that, despite the pain and tragedy that he’s endured, he’s a fun guy. He’s made a certain amount of peace with his lot in life, and he takes pleasure in things like playing piano and flirting with fellow agent Lilly Raines (Rene Russo). He jokes around with Al, he busts chops with his superiors and he cracks jokes left and right. He refuses to let the lousy hand he’s been dealt define him. It’s because of Booth that his demons return to haunt him, and though he has dark, introspective moments, he openly defies them, fighting against the encroaching misery to hang onto his own sanity; this is in perfect contrast to Booth – or, as we ultimately learn is his real name, Mitch Leary – who has been so consumed with the darkness of his own past that he’s become a monster (“…and now they want to destroy me because we can’t have monsters roaming the quiet countryside, now, can we?”). Horrigan carries his own baggage instead of unloading it on the rest of the world, and when he stops the assassination he’s finally able to let it go. Again, this is a much more complex character than he seems on paper, and Clint Eastwood nails every aspect, the humor, the toughness, the pain and the fear, and he does it with the subtlety he brings to all his roles.

***

There are lots of other performances I would’ve liked to add to the list (Hogan, the dynamite smuggling revolutionary from Two Mules For Sister Sara; Philo Beddoe, the bare-knuckle brawler and orangutan befriender from Every Which Way But Loose and the unfortunately inferior Any Which Way You Can; Wes Block, the tortured cop who turns to lust just to feel again from Tightrope; many more besides), but these six are, I feel, distinct in their highlighting of Eastwood’s talent. It’s unfortunate that his acting is dismissed so widely. He’s a terrific performer, able to not only transcend his position as a “movie star,” but use it to his advantage and, when necessary, subvert it to create a character that is as human as he is legendary. When Clint Eastwood appears on screen, we should all feel lucky. Punk.