Tim Seeley Notes One of The Comic Industry’s Biggest Problems

American comic book artist Tim Seeley took to Twitter yesterday with a provocative thought on one of the more significant issues within today’s current comic book industry. Seeley, who is best known for his work on such titles as Batman: Eternal, Grayson, Green Lanterns, and Nightwing, was tweeting in response to a post by fellow comic book artist Jamal Igle. Igle had posted a screenshot of a user commenting on a photo from the official DC Wonder Woman Twitter account with regards to DC Comics and Write Girl collaborating on inspiring creative writing in young girls to potentially be part of the next generation of comic book writers. The original post was likely a knee-jerk reaction to the current state of decline in which the comic book industry finds itself. That said, there is some truth to what they wrote:

“Looks like a bunch of people who couldn’t tell you who Jack Kirby, Alan Moore, or Geoff Johns are. A bunch of people who likely HATE the history of the characters they will be writing for. Where are all the boys?”

Firstly, take a breath and find your chill; there aren’t any boys there because it’s a dedicated girl nonprofit, like the Girl Scouts (oops, maybe a bad example?) – that’s why the organization is called “Write Girl.” Now, let’s get back to the real issue at hand. As mentioned above, comic artist Jamal Igle screenshot and tweeted out with this:

This post was probably written by a guy who doesn't know who Ramona Fradon, Jackie Ormes, Jo Duffy, Annie Nocenti, Alitha Martinez are, either.

Boys don't need support getting into mainstream comics. pic.twitter.com/ELgtf185IJ— Jamal Yaseem Igle, #BoycottJohnBoltonsbook (@JAMALIGLE) August 6, 2019

Not to take away from the accomplishments of the women Igle listed (one of them being the very first African-American female comic strip artist, which is no small matter), but not one of these creators can hold a flickering candle to the creators mentioned in the original post. Jack “the King” Kirby, Alan Moore, and Geoff Johns have created enduring legacies with the work they’ve produced, and there’s a reason that their names are brought up more than virtually anyone else when the topic of comic book writers is being discussed. So while it’s excellent that Igle can Google search female creators in comics, there’s still a point to be had here, which Tim Seeley points out:

“Well, I’ll disagree only in that boys (ages like 10-17) kinda do need help getting into mainstream comics, because they don’t read them. We’ve essentially given up on them.”

Well, I'll disagree only in that boys (ages like 10-17) kinda do need help getting into mainstream comics, because they don't read them. We've essentially given up on them.

— Tim Seeley @C2E2 Artist Alley G-1! (@HackinTimSeeley) August 7, 2019

Nailed it. There’s the rub: boys aren’t buying American comics these days unless their father instilled the habit in them. As another Twitter user points out, they’re gravitating towards Japanese manga and anime instead. This falls in line with current sales data that shows American comics dropping in sales year-over-year, while the manga industry continues to climb. What, then, is the issue? Well, as Tim Seeley pointed out, mainstream comics (mostly) aren’t being made for young boys anymore; in point of fact, they’re barely being created for adult males – the overwhelming majority of the people who buy comics in the first place. So why is this? The decline of mainstream American comic books is truly a multifaceted issue, and it can’t be pinned on just any one problem within the industry, but it’s more than easy enough to focus on fleshing out Seeley’s point a bit deeper.

I’m going to break this up into multiple parts, because, in truth, the reasons for young boys not getting into comic books varies with age. Tim Seeley specifically mentioned the age range of 10-17, but there are micro-groups within that range whose tastes differ with their development, and therefore their avoidance of comics does as well. For the 10-12 years range, we’re looking at what is more or less still considered the “young boys” group; this is an age wherein they’re still watching cartoons on the regular (without being poked at by their friends who also watch the same shows but don’t want to admit it). Their focus at this age is mainly on vibrant and fun humor and antics with a little action and no real emphasis on a deep narrative (even if there may be deeper underlying themes, they’re seldom at the forefront or evident to viewers of this age). They’re looking for Super Friends, not The Killing Joke, and as I’ve mentioned before in my comic books for young readers article most American comic books today are objectively not for children by any stretch of the definition (don’t give your child The Killing Joke or Watchmen, please; that’s just bad parenting). Not only do most comic books not offer colorful panels and more lighthearted stories that would attract these younger boys, but many of them are also presenting the exact antithesis of that. Many comics today are dark, Alan Moore-wannabe character deconstructions of depression, lost hope, and death (I’m looking at you, Tom King; also, you write like a middle school valley girl in the ’90s) and kids simply don’t want that. They just don’t care.

Next, we have the age range of 13-15. These kids are starting to want more action in their media while still maintaining a vibrant and colorful aesthetic. Again, unless you’re reading books from the near-bankrupt IDW line like Sonic the Hedgehog, Transformers, or their Marvel Action series, most comics today don’t do this. This is where the Japanese manga and anime market comes into play. While there is without question a plethora of manga and anime that are flat-out young-adult-to-adult-oriented, there are still so many series that ages 13 and up can get into without worrying about their mom walking in and having kittens all over the floor.

Next, we have the age range of 13-15. These kids are starting to want more action in their media while still maintaining a vibrant and colorful aesthetic. Again, unless you’re reading books from the near-bankrupt IDW line like Sonic the Hedgehog, Transformers, or their Marvel Action series, most comics today don’t do this. This is where the Japanese manga and anime market comes into play. While there is without question a plethora of manga and anime that are flat-out young-adult-to-adult-oriented, there are still so many series that ages 13 and up can get into without worrying about their mom walking in and having kittens all over the floor.

And at last, we come to the final bracket of 15-17-year-old boys. This is an age where maybe they’ve gotten their first job over the summer in between their high school years and can start throwing their own money towards stuff. So, what do they do? Do they rush over to their local comic book shop (if they even have one nearby) and drop their wallet on the counter there? Not likely; if anything, they probably went down to their nearest video game store instead. But why wouldn’t these kids want to read more about Batman, Spider-Man, and the Flash? To be frank, apart from the stories for these characters being uninteresting more often than not lately, the value isn’t there. Four or five bucks for a twenty-something page floppy (most of which is unnecessary dialogue) that will take you maybe fifteen minutes to finish simply cannot hold a candle to the value that an eight to ten dollar manga volume that A) is in many cases 100+ pages, B) offers far more aesthetically-pleasing art to the adolescent eye, and C) the writer isn’t trying to preach to or insult the reader. The focus in manga is always on the characters and the world they inhabit, and the writer always stays in their lane with regards to genre. Indeed, there are manga and anime that have a distinctly political theme and tone, and those that do are almost always excellent, but it is what drives the story forward in those cases and is an essential element to the world that the writer is presenting, and always offers both sides of an issue.

At 17, most people know when someone is taking a jab at them (unless you’re incredibly thick-skulled), and many comic book writers do just that. Comic book writers as of late have utilized their book as a pulpit to preach whatever their ideology is, and the characters within as the mouthpieces for their socio-political agendas, whether it falls in line with that character’s history or not. But beyond even that, teenage boys want something pleasing to look at, and very little in the way of excessive dialogue, and most mainstream comic books aren’t offering that. Manga handles this topic quite differently (maybe a bit overkill in some cases, but if it makes money, then ultimately it makes sense). Make no mistake about it; there are absolutely comic artists out there of titanic talent levels whose styles elevate the books on which they work. But these seem to be the artists who see the least amount of work. For what it’s worth, the comic books of the 1990s and early 2000s understood scientifically who their target audience was, and publishers tailored their books towards them. Teenage boys want to look at attractive female characters; let’s not sugarcoat the matter. They want to see bombshells, and comics of that era (and a few artists still today) used to operate under this knowledge. As an aside, female characters were far from being the only ones that were “sexualized” to the high heavens; take one look at the builds of pretty much any male superhero in the 90s, and you quickly see that artists knew that their female audience wanted to see ripped guys as well.

So, while Jamal Igle can list off a Wikipedia entry of creators (again, not to diminish their accomplishments), he would be remiss to argue against the statistically-backed idea that young boys, whether ten years old or 17, are not being sought as an audience for American mainstream comic books anymore. The manga industry is filling in that void, and as Tim Seeley points out:

Right and I've said that. We, in the West, don't make comics for them. And that's fucked up.

— Tim Seeley @C2E2 Artist Alley G-1! (@HackinTimSeeley) August 7, 2019

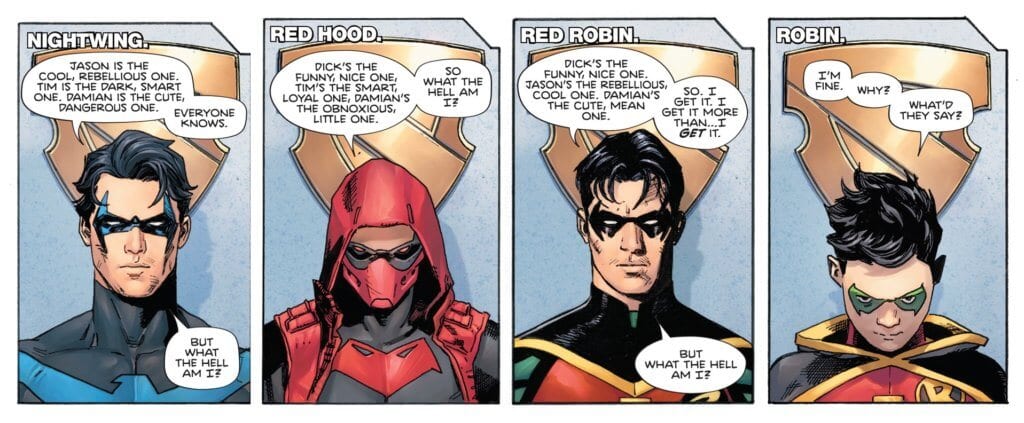

In truth, I’m not entirely sure that publishers know who their audience and market are. They put out books like Ms. Marvel (the Kamala Khan wannabe one, not the best version of Carol Danvers one) and Squirrel Girl, and yet outside of donations to Scholastic book fairs and Ollie’s Bargain Outlet sales, these books are flops. To reference the original post, many writers seem to truly hate the characters they’ve been given the reins to, as they’ll all but destroy Tony Stark’s Iron Man, Thor, and Wolverine, and replace them with lazy, tokenized versions which drive away most long-time readers of those books while attracting few new ones. If DC and Marvel truly want to obtain more female readers, then they ought to be doing more of what was already proving successful: create stories with hot male heroes and present them in a manner that is appealing (seriously, look at most depictions of Nightwing in the 90s and early 2000s for reference if the concept is escaping you), and maybe have a love interest plotline that’s actually interesting. But bear in mind that the female comic book audience doesn’t always require a romance plotline. The females who are into comic books are into them just as they were; there’s no need or point to forcing the matter and expecting to somehow make more sales by appealing to a smaller number of people who already aren’t into the medium at the sacrifice of your base. That’s not how math works, and definitely not how business works.

Tim Seeley is just the most recent industry professional to recognize an issue with the current state of comic books. At San Diego Comic-Con this last month, DC Editor-in-Chief Dan DiDio noted that they’d seen a substantial drop in current comic sales year-over-year while seeing an uptick in sales for reprints of much older stories. Why is this? Well, Dan, it’s because those stories were overwhelmingly more entertaining than the mostly underwhelming and depressing crap that’s being pushed right now. Heroes used to be larger than life. Sure, many, if not all, of them had their struggles and strifes, but those moments of weakness or difficulty were meant to remind us that they were still human (or Kryptonian) at heart. But the point was never to allow those troubles to overshadow the inspiring character that they were meant to be. Former New 52 Flash and DC Rebirth Titans artist Brett Booth, who himself will be penciling a 6-issue Wally West solo miniseries called Flash Forward this September, simplified all of this beyond a yearning for the days of yore. We all want an entertaining comic book, and that means putting more emphasis on the fun action and adventure sequences and less on the diatribe. Character and world-building are important, but not at the expense of what makes superhero comics fun in the first place.

Honestly I don’t think it’s nostalgia as much as people wanting action adventure stories. Modern comics seem to have lost that aspect and are now more focused on interpersonal relationships. You can do both and should do both.

— Brett Booth (@Demonpuppy) August 8, 2019

Every young kid needs a hero of some sort, a role model that they can look up to and be inspired by (and I’m sorry, Gillette; it isn’t you) that teaches them to help others and always put what’s right ahead of all else. Comic book heroes used to be just that and do just that, but it’s something that they’ve gotten away from. Now, instead of inspiring tales of mystery and fantasy with the message of persistent hope, we have nothing but depression and loss, and the heroes that we’ve come to love in a constant state of personal crisis. Problems are real, and the world is chock-full of things to be worried about, but if there’s never any light shown at the end of the road, then you’re never going anywhere except down a dark path, and there isn’t anything inspiring or hopeful about that.

Comments (4)

Hi! Thanks so much for taking the time to give this a read! I’m thoroughly glad that you enjoyed it.

You mention once that Igle probably Googled the names of the female creators, and then later on say he checked Wikipedia.

I find that hypothesis baffling. Igle is an industry pro who has been around for years and knows the players. The women he listed are not Z-listers. Jo Duffy had a memorable run on Power Man and Iron Fist in the Bronze Age and was the last regular writer on Marvel’s Star Wars before Marvel gave up the license in the 1980’s. Ann’s run on Daredevil was the first memorable run after Frank Miller’s and she created Typhiod Mary…one of the creepiest Daredevil villains and one of the few latter day created DD villains to stick around.

Is it that hard to believe an industry mainstray like Igle wouldn’t know who they were???

It’s not so much meant to be taken literally as it is as a commentary on how out-of-touch Igle is with the fans and the industry as a whole. Knowing the names of other creators and their respective accomplishments is well and good, but he’s missing the larger point. Nothing about what I said referred to those creators as “Z-listers,” in fact, I noted that they were indeed important parts of the industry’s history and to that point, you’re absolutely correct in what they brought. However, that was not the point of the article and again it was meant to be used as a measuring stick against Igle’s level of touch with the fans – which he is far from given his responses in the referenced Twitter thread. Thank you, sincerely, for taking the time to read through the piece.

Good read. Props.